|

Am I truly known -

To myself and to others? I don’t think I am. I don’t think I will ever be. But I am not alone. I am a part of a club that spans continents and generations, Starting from the first person who was a person and not an ape anymore, Whose mind opened its wings, so strange and new. From then on, throughout history, How many people do we really know? First, we wrote books about some. Then we realized that so many important others had been left out. Now we are hastily adding them. But can this task of remembering ever be completed? Like the wings of a butterfly, Smallest actions can cause big effects, Connections no one will know about. Imagine how many people have lived on the Earth: Laughed and loved, Healed and hurt, Hoped and despaired, Tried and failed, And sometimes succeeded. They all have mattered, In ways beyond good and bad That nobody will ever fully grasp, Because a hurricane cannot be traced back To the butterfly that caused it. We will sing songs about heroes and villains. We will disagree on who our heroes and villains should be. That’s okay. Disagreeing is human. But I hope that we can also agree on something: You, and I, and the infinity of souls Will remain unknown To ourselves and to others, Yet we all matter. Beyond good and bad, We are forever tied together in the fabric of humanity. I hope that once in a while, You can light a candle, or plant a flower, Or just sit for a few minutes in silence, Quietly wondering About all the butterflies That have ever danced in the wind. *If you liked the poem, you might also want to watch the video below, where I where I read the poem to the beautiful music by Maarten Schellekens.

0 Comments

Louis XIV is probably one of the most famous kings associated with the idea of absolute monarchy. Many people probably believe that he had absolute (or at least almost absolute) power. Among scholars, however, it's not uncommon to point out that the power of absolute monarchs (in fact, of any kings) was limited. In my own scholarship, I explore the idea that power always coexists with powerlessness. I decided to take Louis XIV as an example to show what this might look like. I figured that some people might be intrigued by the idea that this famous king could be described as being powerless in some ways.

I carefully read a very detailed account of Louis XIV's life and reign by a historian Philip Mansel. His account is based on thorough research of numerous sources. Then I wrote an essay using quotes from Mansel's book to support my claims. This essay turned out to be the longest one I have written so far. It is still not entirely finished. I feel that my argument could be further improved, but I feel that I need to step away from this project for a while. So I am going to share with you what I have so far. As I write in the introduction of the essay: "I must clarify that any historic account can only be a work of interpretation... I acknowledge that it is my choice not to see Louis XIV merely as a haughty and heartless lover of exquisite entertainments. Instead, I choose to see him as a person who, like all of us, was born into the world of meanings and relationships that he did not fully comprehend. He tried to navigate this world the best could, in the process making many mistakes and hurting numerous people, which he was able to do due to the meanings of absolute monarchy instilled in his mind and reinforced by those around him." You can click here to see the whole essay. Below I am am going to share the part that I titled "King's Childhood". ******************************************* When his father died in 1643, four-year-old Louis XIV was proclaimed King. Of course, he did not start managing France right away. Upon the death of her husband, Queen Anne became the regent, ruling with the help of Cardinal Mazarin until Louis reached the age of majority (13 years old) in 1651. After that, although his mother was not a regent anymore, the young King did not fully take state matters in his hands for another ten years, until Mazarin passed away in 1661. Let us first take a look at the formative years of the future self-proclaimed Sun King. We could hardly claim that Louis XIV came anywhere close to absolute power as a child. But as King by law, perhaps he enjoyed a life of exceptional happiness and freedom? Chapter I of Mansel's volume dispels this myth starting from the first sentence: "Even by royal standards, the family into which the future Louis XIV was born on 5 September 1638 was a nest of vipers." In this family (not atypical for a royal household of the time), closest relatives often could not trust or even stand each other. Intrigues flourished and rebellions were common. Queen Anne herself, being of Spanish origin, conspired against her husband (Louis XIII) and helped her home country during the conflict between Spain and France that was ongoing at the time. Driving this point home, Mansel writes in the Introduction: "Thus antiquity, heredity, coronation and the widely proclaimed belief that the kings of France were representatives and images of God himself did not protect them from rebellion or assassination. France was a monarchy on a knife-edge... Both Henri IV’s son Louis XIII and his grandson Louis XIV would be threatened by repeated revolts and haunted by fears of new religious wars and acts of regicide." All in all, Louis XIV's family could hardly be called a healthy environment for a young child trying to make sense of the world. Consider that, as Mansel argues, "[e]ven at the age of two, Louis was a pawn in his parents’ marriage. His feelings and manners were used as political weapons" (Chapter 1). The French court where this family was embedded was no better. "[A]t the French court every nuance of human relationships, and every inch of the royal apartments, could have political consequences. The court was a zone of negotiation, and a school of psychology, as well as a battlefield" (Chapter 1). Louis XIV had to navigate this battlefield, or rather minefield, of a court from a very young age while attending a variety of required events. As he was growing, his public life was quickly turning into "an unending sequence of ceremonies" (Chapter 2), which he soon came to detest but could not avoid. One can only wonder how becoming a king at the age of four can affect a child. No psychological studies that would help us better understand what it really means to grow us as an absolute monarch can ever be conducted. But it is clear that, before Louis XIV could start exercising his power as a king, he received many lessons in powerlessness. On the positive side, he had a close and tender relationship with his mother, something that few (if any) contemporary kings could boast. Unlike many royal parents of the epoch, Queen Anne spent a lot of time with her beloved first-born son and played an active role in his education. In particular, she worked hard to instill in Louis the belief in the divine rights of the King of France. Queen Anne, who had experienced her own share of powerlessness, wanted absolute power for her son, probably because she believed that power could protect him and make him happy (these wishes are natural for any caring mother). We can assume that her lessons sank deep and determined how Louis XIV wanted to see himself and to be seen by others. Over the years, the conviction in his divine rights coupled with life's stresses, heartbreaks, and very human biases led Louis XIV to commit mistakes that hurt numerous people. One of these heartbreaks was his mother's painful death at the age of 64 (Louis himself was only 28 at the time) of breast cancer in a Parisian convent, where she had retired after her regency was over. Louis XIV was so shaken by her death that he barely visited the city since then, preferring to enhance his beloved Versailles and surrounding smaller residences. There is another reason why Louis XIV hated Paris, and this reason further illustrates why his childhood was far from carefree. Mansel describes France's capital as "a cauldron of combustible institutions, at once the support and rival of the monarchy" (Chapter 2). Indeed, support and rivalry were often tied so close that this combination could easily become confusing, frustrating, and scary. The King would be glorified when riding through the street of Paris one day, but booed and threatened on another occasion. He was alternatively treated as god and as the worst person on the Earth. For instance, "On 18 May 1643, three days after his state entry into Paris, Louis proceeded from the Louvre through the streets caked in mud and excrement, for which Paris would remain notorious until the mid-nineteenth century, to the Parlement on the Île de la Cité" (Chapter 2, my emphasis). Before Louis XIV reached the age of majority, Paris became a hotbed of dissent known as the Fronde. It was essentially a civil war. The Fronde was not a bottom-up rebellion; instead, it was led by aristocracy dissatisfied with their rights and privileges. The noblemen exploited popular discontent among Parisians who were not happy about growing taxes and diminishing authority of the Parlement. Notably, when Louis XIV was 12, an angry mob broke into the capital's palace and demanded to see the King. Upon seeing the boy sleeping in his room, the rioters left the palace. Soon thereafter, the Queen and her son fled Paris accompanied by the court. On another occasion, Louis XIV and his mother were held in the same palace under virtual arrest. This is not to say that Parisians did not have reasons to be concerned about the actions of the government trying to centralize its authority (something that absolutist monarchies were known for). Without excusing the French government's actions, my goal is to have my readers wonder how confusing messages and events of the time could affect the King's maturing mind. (And remember that, at that point, he was not the one making decisions about how France was supposed to be ruled.) We can assume that the idea of the King's divine rights was attractive for the growing Louis XIV as it promised certainty in a life full of conflicts and contradictions. In addition, the idea of the King's absolute power matched what Louis XIV often observed, since "[f]or most Frenchmen in the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Christianity and monarchy were similar cults of hierarchy and obedience" (Chapter 1). Any rebellions and riots (even as extensive ones as the Fronde) could be written off as unpleasant aberrations. Inspired by his beloved mother, Louis XIV was growing up with the conviction that he was destined to become the King of the World. He was learning about his rights and responsibilities. But nobody could explain to him how the power he had been given was going to change him over time. Click here to keep reading. Thank you for your interest! *This post is a part of my project Me, Looking for Meaning.

The phrase "give somebody credit for" has two meanings. First, it can mean believing that somebody has a good quality. Second, it can mean praising this somebody for an achievement. And praising can also implicitly mean comparing one(self) to others who supposedly did not do as well. So, the title of this essay has two interpretations: (1) Am I empathic? and if the answer is "yes", (2) Can I, metaphorically speaking, pat myself on the back for being empathic AND compare myself to somebody else who seems to be less empathic than me? I think and write about empathy a lot. Usually, I believe that empathy is my strength, a skill that I can develop in myself and, indeed, keep developing. But I also have plenty of doubts in my ability to be truly empathic. I want to think of myself as being fairly good at using empathy. However, I often catch myself focusing on my own emotions and experiences instead of feeling more with others or trying to understand what they are going through. (Side note: in this essay, I describe empathy as a useful skill, which is itself an assumption that not everybody agrees on, although in some cases this might be just a semantic disagreement after all.) I see empathy as consisting of two aspects: cognitive and emotional. It's a way to connect with others on an emotional and/or intellectual level, to peek into the window of their world, so to say. I think that I can be a fairly empathic person because I do my best to remind myself that my perspective is only mine, to remain attentive to and curious about other people's worldviews, even if I do not quite like them (these worldviews or even the people who have them) for some reason. I believe that my empathy (when I manage to do it right) helps me stay connected to others, avoid blame by remaining curious about other people's actions, and keep an open mind, which allows me to learn and grow. Even if I am overwhelmed with an emotion, I am working on staying in touch with what's going on in another person's head and heart. Thinking about the past, I notice that developing this level of empathy has been a journey. My memory offers some painful reminders of situations when I did not sufficiently care about how other people were feeling. The more I go back, the more painful these memories become, but then I remind myself that empathy is a skill that requires honing. And as with any skill, having trained yourself in empathy does not mean not making mistakes when using it. If anything, awareness about my mistakes in the past, and even in the present, helps me to keep learning. But even if we decide that I am an empathic person after all, the second interpretation of the title question remains: Can I praise myself for my achievements? To remind you, what makes this question controversial (in my mind) is the implied comparison with some others who are supposedly less empathic than me. Does striving to be empathic and actually being empathic make me a good person, better than those less preoccupied with honing this skill? If you know me a bit, you won't be surprised when I say that I don't think that I am any better than someone who does not use empathy that often, someone who does not think that empathy could be improved and is, indeed, worth improving. Yes, I work hard on being more empathic, but in a way I just happen to be more preoccupied with it than some other people are. If I observe somebody who does not seem to use empathy as much as I do, I have two main options: (A) I can say to myself, "This person is just not sensitive, they just don't care, they don't want to help, they are just making it worse, etc." (B) Or I can say to myself, "Empathy is hard. I struggle with it all the time. They must be overwhelmed with emotions, and I know how it feels. There must be something going on in their lives, or something from their past, that would explain why empathy is so hard for them or why they don't see its value." (Admittedly, I would be making an assumption that the other person in this situation is not using empathy, which is my interpretation entirely. They might be using it but in a way that makes sense to them.) ...I see this complexity as part of a much bigger conversation about free will. In general, when other people behave in ways that (we think) are not ideal, we can either explain this behavior by claiming that these people are inferior: "they are mean", "they are just stupid", "they are not normal." Or we can explain their behavior by taking into consideration a combination of (1) circumstances outside of these people's control combined with (2) some element of choice, and by admitting that the ratio of these elements is unknown to us. I believe that people do make choices, and that's why I am personally striving to be more empathic: I believe that empathy is a choice I can make, a sort of power that I can develop. But I also think that our actions, thoughts, worldviews, and even desires are shaped by our environment. So if I value empathy or find it easier than others to be empathic (ok, not always), there must be something about my genetic makeup, my upbringing, my experiences, rather than a fully controlled decision that I made (or make)--a decision that which would put me on some kind of pedestal compared to others who might not be as good (arguably) at empathy as me. And really, can I give myself credit for anything good about me, for any of my achievements? For example, I am fairly organized in my work. Does it make me better than someone who often procrastinates and leaves projects unfinished? Or how about my ability to focus on and enjoy all the little things I see? I believe that this ability greatly helped me when I started learning about mindfulness. I probably made some choices along the way that helped me develop my ability to be mindful and self-aware. But I can assume that there has been something in me (e.g., the way my brain can focus on these details and enjoy them) that determined my openness to the idea of mindfulness. We can assume that there is some element of choice present in our actions, but the exact scope of this choice is hard to identify. There is, on the other hand, a great deal of determinism, including individual nuances of how every person's mind works, values we were taught growing up, coping mechanisms we were able to develop based on our experiences, etc. Even choices we made are often determined by circumstances that we would not be able to fully wrap our minds around. So, I do not think that I can take full credit for my ability to be empathic, or for any other good qualities I might have. I might be able to take partial credit, though, but the vagueness of free will does not allow me to be more specific about the praise I might deserve. Just as I cannot be sure how much I can praise myself for my good qualities, I cannot ever be sure how much somebody else could be criticized for not having these traits. It is very possible that this somebody could not be rebuked at all. (Again, I am not even getting here into the thorny conversation about what makes a quality "good". I might think that I have good qualities, but somebody else would disagree. And who's to judge?) Since I cannot take full credit for what I can do, I should also avoid looking condescendingly at people who do things differently. It is true that these people did make some choices in their lives, but many of their choices were constrained (so were mine). And if free will had been involved, I will never know when this freedom began and when it ended. Keeping this complexity in mind gives me further reasons to be more humble and curious about other people. I might not fully understand their circumstances, but I can give it a try; at the very least, I can acknowledge how little I know. To make a full circle: acknowledging that I cannot give myself full credit for being empathic is, in my mind, an essential aspect of developing my empathy. I am kind of obsessed with power. I think about it every day. Not because I am bent on achieving world domination! My interest is scholarly, and it is connected with very practical concerns about the world we all share. However, this connection is probably not what you might think.

“Power” is an incredibly rich concept. We can talk about it in the context of military dictatorships — or of an individual’s (potential) ability to escape the claws of anxiety. We can consider the importance of power balance in intimate relationships — or the popularity of superpowers in modern media fairytales (and also the power of media companies that produce them). There is power of speech and power of hope; power of mind (e.g., intelligence) and physical power (e.g., weight-lifting). While some of these things seem to be similar, others — not so much. Perhaps “power” is just a word that has numerous meanings, many of them unrelated? After all, it is also used to talk about electricity, an order of angels in Christianity, and the process of washing cars with highly pressurized steam (the list goes on). Setting aside the meanings that do not directly describe people and their relationships, I believe that all the aspects of power — ranging from political to personal — should be explored together. So, yes, military dictatorships cannot be tackled if we don’t consider the power of mindfulness. The goal of this exploration is not to forcefully connect some random dots that just happen to have the same label. The goal is to better understand each other for the purpose of living better lives in a healthier society. To keep reading on Medium, click here. Or listen to me reading this essay out on Spotify!

Where are you now?

The sand of years has slipped through our fingers somehow. The words we tried to use as bridges between us-- They don’t mean what they meant before. The stars we thought were guiding us aren’t there anymore. We were once friends. Or were we? I don’t know. Time can be just like sand or it can be like snow. It covers quietly our memories, our dreams. We were once friends. Or so it seems. The world has changed. The world has rearranged itself. The paths you used to walk, lead somewhere else. And if I wanted to find you, I wouldn’t know where to start. But I don’t want to look for you. You are someone new. I’m someone new. And still, I don’t know why, I don’t know how, The thought comes back: Where are you now?

As time goes, relationships change. Connections that once seemed special and strong slowly dissipate. You reach a certain age and start wondering, "Where are all these people I once knew?" You might even have a sudden urge to find them and talk to them again, see if those friendships and feelings can be rekindled. And sometimes it works, sometimes it's worth doing. But often you just have to let it be. Focus on the connections you have right now. And still, once in a while, you will think about some person that was once important to you and wonder, "Where are you now?" In this poem, I wanted to capture this feeling of wondering mixed with bittersweet sadness of letting go of a relationship that was once special.

For almost two weeks now, my heart has been heavy. I have questioned my right to be happy at the time when others are suffering. It feels selfish, but I must go on. At the time when living a “normal” life seems like an extraordinary privilege, writing is one thing that helps me keep some sanity. If you follow my work for a while, you will see that writing for me is not an escape from the world’s problems but but an attempt to understand them and, in the long run, hopefully to offer some solutions. (Perhaps that’s too ambitious of me, but still, I let myself run with this idea. Perhaps it’s just another way for me to keep my sanity somewhat.) All that said, I am introducing a new entry in my hypertext project about power. Michel Foucault: "Power Is Everywhere"I will not tell you to read books by Michel Foucault –unless you already tried and liked them. Not because I think that this postmodernist French philosopher is no good. On the contrary, in my opinion, his works contain precious clues for understanding people and their relationships. But, to be honest, Foucault's books are hard to get through for anybody without special preparation or inclination (or even with those!). That said, I am going to quote him below (sparingly) and explain why (I think) his ideas are so important. I first heard about Foucault back in Russia at St. Petersburg State University in the early 2000's. While my professors were raving about him and French postmodernist philosophers in general, I was frustrated and confused by this school of thought. Still, one of Foucault's ideas stood out and stuck with me, probably because it came with an intriguing mental image. Foucault, I was told, wrote a lot about power. Among other things, he wrote that power is like a flow that is constantly moving though society. It never solidifies, although it does sometimes concentrate in certain "nodes" of the social system. Foucault certainly did not deny that power inequalities and abuses exist, but he was also apparently saying that things are more complicated than they seem to be. This image of fluid power was stored in my memory until I started writing my own book (about media). In that book, I attempted to explain my position as a paradox: On one hand, we need to acknowledge problems associated with media and work on fixing them. On the other hand, blaming certain individuals or groups for creating these problems will not bring us closer to any long-term solutions. This was, essentially, a conversation about power. We blame somebody when we think that they have power over the situation (they caused it or they do not want to change it). And I was trying to explain that blame is unhelpful because things are more complicated than they seem to be. It is not just us vs. them, we are all in this together. It was at that point that Foucault's ideas about fluid power came in handy. Image credit: Solen Feyissa Foucault's book The History of Sexuality, Vol. I: The Will to Knowledge contains an oft-quoted phrase: "Power is everywhere... because it comes from everywhere.” What might this mean? To me, Foucault's most crucial contribution is that he challenged what I call "binary thinking about power". In other words, he challenged the idea that power is simply what some people have and while others don't. Instead of seeing power as concentrated (centered) in certain social institutions or in some people's hands, Foucault suggested that power is de-centered, and that it does not belong to anybody in particular. He wrote that power is not a static system but rather a kind of ever-changing flow. At the same time, he did not say that power is equally distributed throughout society at any given moment. Inspired by Foucault's ideas, in my book Media Is Us I included a chapter titled "Paradoxes of Power." I argued that we should certainly talk about injustices and do our best to correct them, but we should not hope to solve society's problems simply by dividing people into villains –who have power and abuse it– and victims –who lack power and suffer. (In an interesting twist of events, Foucault's ideas about power have been used by some critical theory scholars in ways that have actually reinforced the binary thinking instead of further challenging it. This contradiction makes more sense if we consider Foucault's elaborate writing style, which opens possibilities for different –sometimes contradictory–interpretations of his work. Another reason might be that Foucault never proposed a coherent theory of power unifying different ideas about this major concept.) So what exactly did Foucault say about power in The Will to Knowledge? (If you need to find an exact place in the book: Foucault's ideas about de-centered power are explained in Part 4, “The Deployment of Sexuality”, and even more specifically, in Section 2, titled "Method".) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy gives us the gist of Foucault's argument: "We should not try to look for the center of power, or for the individuals, institutions or classes that rule, but should rather construct a 'microphysics of power' that focuses on the multitude of loci of power spread throughout a society: families, workplaces, everyday practices, and marginal institutions. One has to analyze power relations from the bottom up and not from the top down, and to study the myriad ways in which the subjects themselves are constituted in these diverse but intersecting networks. Although dispersed among various interlacing networks throughout society, power nevertheless has a rationality, a series of aims and objectives, and the means of attaining them. This does not imply that any individual has consciously formulated them." Image credit: arturo aguirre The Will to Knowledge is a book about sexuality, a topic which Foucault was keenly interested in as a gay man. However, rather than citing Foucault's examples related to sexuality, I will talk about de-centered power by using a comparison of a king vs. his subject (for example, a peasant). I am especially interested in the way Foucault challenged the binary thinking about power –the idea that people are divided into those who have power and those who don't. I like the king vs. peasant comparison because it is one of the most extreme examples that come to mind when one thinks about power as a binary: the king is the powerful one, while the peasant is powerless. The binary thinking about power goes like this: Those who have power (e.g., kings) use it to (a) keep this power and (b) make others (e.g., peasants) do things that those others often do not enjoy doing. So the king will write laws to make sure that, if peasants are unhappy, they will not come and take his crown away. This repressive power does certainly exist, according to Foucault, but that's not necessarily the kind of power that deserves most attention. There is only so much you can do by force. Foucault suggested that we should analyze power relations not just from top down (how the king controls his subjects) but also from bottom up (e.g., how his subjects' actions make monarchy possible). Focusing on the repressive power used by the king (e.g., chop off the head of anybody who conspired against him) will help us get only half of the story. We should also explore how power grows from the bottom up –for example, how some peasants' sincere veneration of the king, despite all his laws and decisions that hurt them, supports the monarchy. In other words, power is not only simply embodied in and wielded by the king. Paradoxically, power that the king uses is not entirely his to begin with. This power is made possible through actions of many other individuals, from the very bottom of society to its very top. In some ways, the king is not in control of his own power because he was born into his social position the same as the lowliest peasant was. The king is often a prisoner of society’s rules that he did not create, he does not fully understand, and that he does not even always benefit from (I will explore these ideas in more detail on the upcoming page about Louis XIV and absolute power). Foucault suggests that top-down power coming from some specific center would not be able to use repression to achieve or maintain control. He specifically argues that there is no top-down duality in power. In other words, power is not something that spreads from the very top to the lowest and least powerful layers of the social system. In this sense, Foucault could say that it was Louis XIV's wishful thinking to imagine himself as Sun King (le Roi Soleil), with power emanating from his authority like light from the sun, moving to whose close to him and from them further and further away till the rays reached the deepest layers of society. Image credit: Jonathan Borba According to Foucault, rather than being repressive and centered, power exists through an interplay of various social forces. This interplay is changing from moment to moment in each relationship and is, therefore, unstable. Here is what the oft-quoted phrase by Foucault looks in context: “[Power] is produced from one moment to the next, at every point, or rather in every relation from one point to another. Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” A few lines later he continues: “Power is not something that is acquired, seized or shared, something that one holds on to or allows to slip away. Power is exercised from innumerable points in the interplay of non egalitarian and mobile relations.” According to Foucault, power is not about external control or prohibition. Power should not be imagined only as a king punishing his subjects for their transgressions. Power is productive, it creates rather than simply negates and limits. In this sense, everyday actions of the king’s subjects make the monarchy possible the same as (or perhaps even more than) the punishment of those subjects who dare to question the king’s authority. Foucault challenges the binary thinking about power quite literally by saying: “Power comes from below. That is, there is no binary and all-encompassing opposition between rulers and ruled at the root of power relations.” This does not mean that the king's subjects do not suffer from his laws and decisions, or that the king does not enjoy his authority. It would be wrong to interpret Foucault's ideas as suggesting that, because there is no binary opposition in power, there are also no inequalities. But the root of these inequalities is not in the power as binary, so they cannot be resolved if we only focus on the binary opposition of the powerful vs. the powerless ones. The crux of the paradox laid out by Foucault can be difficult to make sense of. He wrote: “Power relations are both intentional and non subjective.” This can be interpreted as Foucault saying that people –both kings and their subjects– are not some kind of automatons: they do have plans and they make decisions. However, paradoxically, their choices are not always entirely theirs. Power is "non subjective" in the sense that nobody is entirely in control of the situation even if it seems that they have quite a bit of power to change things. (This is related to paradoxes of free will that I introduce elsewhere.) Image credit: Pixabay

The following passage appears to support this interpretation (emphasis mine): "There is no power that is exercised without a series of aims and objectives. But this does not mean that it results from the choice or decision of an individual subject. Let us not look for the headquarters that presides over its rationality. Neither the caste which governs, nor the groups which control the state apparatus, nor those who make the most important economic decisions direct the entire network of power that functions in a society and makes it function. The rationality of power is characterized by tactics that are often quite explicit at the restricted level where they are inscribed... tactics which, becoming connected to one another, attracting and propagating one another but finding their base of support and their condition elsewhere end by forming comprehensive systems. The logic is perfectly clear, the aims decipherable. And yet it is often the case that no one is there to have invented them and few who can be said to have formulated them." Foucault's interpretation of power raises several important questions. If no individual is completely responsible for how society functions, why is society the way it is? If nobody is fully in control, can anybody be held accountable for some individuals' discomfort or sufferings? We wouldn't blame people for their own misfortunes, would we? If nobody is in control, how can we hope to change things? Can we change things?? These are some of the questions that I attempt to answer with my own theory of power... SOURCES: Foucault, M. (2012/1976). The history of sexuality: An introduction. (Trans. by R. Hurley). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (last updated August 5, 2022). Michel Foucault.

It is mind-boggling to think that I have lived in the United States for 12 years now. It is equally strange to tell myself (and other people) that since then, I have been back to Russia, my home country, only once. It was 10 years ago. And it is sad to admit that I am not even sure when I will be there next time.

Do I want to go back? If I really really wanted to, I would find a way. It would be a lie to say that I do not care about the country where I spent the first 27 years of my life. I do not want to live there right now. But if I had a magical teleportation machine, I would certainly love to revisit places when I once was so happy and so sad. I only I could... But wait! There is a way. I can teleport myself to all those places in my nightdreams. These visions have a strange relationship with my memory. Over the years, I discovered that dreams took over. Now I am not even sure whether I remember correctly all the streets where I used to walk. Perhaps what I "remember" is just a figment of my imagination? When I first came to the United States, for the first few weeks I had a lingering feeling that I was in a movie. When (if) one day I go back to Russia, it will probably seem that I found myself in a very very long dream. This poem is about the impossibility of returning to the past of a place and of the self. All of us have experienced a version of this feeling, no matter whether we are immigrants or just moved to a different part of the same country. One day we all discover that it is impossible to stop the clock, to go back to where and who we once were. This realization does not have to be painful. There are always memories to treasure and things to look forward to. *Watch the video above to hear me read this poem to the beautiful music created by Maarten Schellekens. One day, I will return… No, this is not the right word. “Returning” Means coming to a place where I once was. But it does not exist because My memory has turned it into rain... Let’s try again: One morning, when I walk Along the streets that bear deceptively familiar names, Some even hiding echos of my childhood games, I’ll look into the eyes of buildings that will seem So real yet hard to grasp, Like an unfinished dream. Let’s try again: One evening, when I step Onto the floating island of my past, So infinite and yet confined, Packed tightly in the nutshell of my head. Will I be home at last? Will I be whole at last? Let’s try again: If I could choose Of all the places that my memory holds, Where would I go? I know: The sprawl Of the old park where I once learned To find birds’ nests and mushrooms under trees And where, on a hidden path, A sculpture of a giant’s head Teased me with mysteries. I think this time I got it right: When I am old and when my head is light, I’ll dream myself next to the giant’s face Half-buried in the middle of the path. Once there, I will remove, as one takes off a robe, The layers of years and skin And will emerge Among soft shades of leaves, a child again, Ready to soak in the gentle sun, Forgetting what my older self has done. The journey’s over. I’ll stay there Alone, Letting warm breeze play with my hair. I have two updates:

1) about the contents 2) about the newsletter I have had a few weeks free from work (I am a freelance editor, and sometimes I have time between projects). During these weeks, I have focused on writing for my project POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. In fact, I realized that this is a project that I want to focus on for a while. My second hypertext project Me, Looking for Meaning (chronologically, it was actually first) will take a back seat. It has been tremendously important for me, especially since it helped my project about power to take off. But, for the sake of efficiency, I want to focus on one thing for now. This change means that many of the new blog posts will be related to POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. I hope you share my interest in this topic and will be excited about new pages of the power project. I will occasionally post other things. For example, I have finally been able to organize my Russian poems, so I plan to translate more of them and even turn some into videos. I also plan on creating and sharing some videos based on my English poems, of which I still have only a few. If you would like to be notified about new blog posts, I have great news! This change was inspired by my friend Jiwon, who is working on an important hypertext project about life and experiences of a North Korean defector Kumhee. After browsing their website, I realized that I need a newsletter! Now I have one. You can sign up by scrolling to the bottom of the main blog page (or my About page) and entering your email. This way, I will let you know about new blog posts. I will send out the newsletter no more than once per week, probably much less often than that. And you will be able to unsubscribe at any point. I hope that you will join me on my intellectual journey! I appreciate you support :) *This is a new entry of my hypertext project POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Free will is the focus of one of the longest-running debates in the history of human thought. This debate is shaped by two main questions: Are people's decisions and actions independent from any circumstances? Are people's decisions and actions predetermined? On this page, I present the debate about free will and discuss how it is related to my exploration of power. For a more thorough overview of the free will debate (i.e., different schools of thought, positions of specific scholars) see the sources at the bottom of the page. It is important to keep in mind that the debate about free will belongs to the realm of philosophy. That is, we cannot declare with absolute certainty whether free will exists or whether it is a myth. It is possible that answers to the debate's questions elude us due to the limitations of the human mind. Another possibility is that the main dilemma of free will is formulated incorrectly. In other words, it might be pointless to argue whether people are absolutely free in their choices or whether their actions are completely predetermined, since both of these options are neither true nor false. Why might we assume that people are free in their decisions and actions? This is what our intuition is telling us. Just to clarify, I am not talking about enslaved individuals, but about an average person living in a democratic country. If you ask such a person if their decisions and actions are free most of the time, they will probably say yes. Or this person might tell you that their decisions and actions are not always free because they often have to do things that they are expected to do (by their family, community, organization they work for). But they will also probably tell you that they know when they are making a free choice vs. when they do something because they have to do it. In other words, they will tell you that they can use their free will sometimes and that they know when they use it. If after reading this page, you want to test how you yourself feel about your own ability to make free decisions and take free actions, you can pay attention for a few hours or a day to things you do, including the smallest actions throughout your day. You will probably notice that many if not most of these actions appear to be a result of your free will. In other words, you will feel that you do them because you want to do them. (In fact, if you feel that most of your actions are a result of somebody forcing you, that might be a symptom of a serious problem, either related to your mental state or to your relationships with people around you.) Why might it be a problem to assume that people are free in their decisions and actions? If you feel that most of your decisions and actions are free, you will most probably assume that other people's decisions and actions are free most of the time as well (we are talking about free people living in a free country). The problem with this assumption is that it can lead to negative emotions directed at other people or to the reluctance to help people experiencing problems. For example, you might say that people who are poor are to blame for their economic situation. Or that people who have achieved less in life than what you have achieved are just lazy; they could have made different choices and become more successful, but they chose not to. As a result, you will be less willing to support people who are struggling. You will feel superior towards people who, you will feel, have achieved less in life than you did. Believing in free will might be unhelpful also because it can create unrealistic expectations about willpower. For example, we can beat ourselves up for our inability to break a loop of a habit (e.g., smoking or overeating). We will expect ourselves to control our impulses just by deciding to do so and by formulating logical arguments why we should not do something that harms us. As a result of this self-judgement and pressure, we will not be able to find effective ways of breaking out of our habits (this idea is discussed in the book Unwinding Anxiety). Why might we assume that people's decisions and actions are predetermined? On the other hand, we might want to take into consideration various circumstances influencing our decisions. We are born into the world of social interactions shaped by spoken and unspoken rules. Our actions need to be aligned with ideas that we did not create and often do not fully comprehend. Our actions are determined by our perceptions. But where do our perceptions come from? Anaïs Nin famously said, “We see the world not as it is, but as we are.” To that, I can add that the way we are is in many ways shaped by the way the social world around us is. One might assume that our desires are free: I want something because I want it, not because somebody told me to. So actions based on desires are also free. But our desires are in many ways biologically and culturally determined. Think, for example, about desires based on survival needs (both individual and the species), which shape our decisions about looking for and keeping a sexual partner or about foods we crave (e.g., the fact that most people like sugary and fatty foods is related to older parts of these brain that associate these foods with survival). Although our needs are not only related to survival (see Maslow’s hierarchy of needs), the "higher" needs often reflect the social world around us. For example, to fulfill the self-actualization need ("desire to become the most that one can be") one has to have some understanding of what this "most" can look like; this understanding often comes from the larger society and communities that one feels a part of. It is nice to think that, as the famous protest song goes, "Die Gedanken sind frei" - which means "Thoughts are free". But how free are they, really, if they reflect cultural meanings that we did not create? How free are our thoughts if they are shaped by biological needs that all representatives of Homo Sapiens species share? How free are really our thoughts, if they are influenced by emotions that we find so hard to control? Why might it be a problem to assume that people's decisions and actions are predetermined? If we accept the idea that our actions and their results are predetermined, we might be less willing to change our lives or challenge ourselves. We might think: "If whatever I do leads to the result that I have no control over, why bother?" This assumption might spell doom both for individual and for social development. Belief in determinism might also lead to denial of responsibility for any actions. How can we expect anybody to be accountable for anything if we believe that nobody can act differently from how they act (due to biology, socialization, and personal experiences outside of our control)? This point of view might lead to passivity in the face of any injustices and inequalities. If all our actions are predetermined, we cannot either request accountability or give people credit for any accomplishments. No matter whether we see the result of a certain action as "good" or "bad", we might need to acknowledge that this action was taken not because somebody made a decision to take it. According to determinism, the real reason behind any action is a chain of events outside of any individual's control, set in motion in the beginning of the universe. * * * The debate about free will is going to remain purely philosophical unless we find a way to scientifically test if our desires and actions are fully predetermined or not. To test this idea even for a seemingly simple action, like you reading this page right now, we would need to take account everything that has happened in the universe from the beginning of time and see if all of these events lead with absolute inevitability to the the action in question, or if there is a wiggle room for free will undetermined by the circumstances of the past and present. At best, we can only have logically-grounded but untestable opinions about free will.

In my opinion, we should assume, for practical purposes, that both absolute free will and absolute determinism do not exist. I believe that our actions are shaped by some amount of what can be called "determinism" and some amount of what can be called "free will". In other words, it is hard (in my opinion) to deny all the circumstances that shape our actions. We are not absolutely free to make any possible decision, we are not even absolutely free to envision or desire any possible decision. In terms of my exploration of power, we can say that everybody is to some extent powerless in the face of numerous circumstances outside of our control. On the other hand, I believe that there is wiggle room in our actions where we can make choices that affect our life and lives of people around us. Free will happens only within the wiggle room because our choices are not entirely free. We can choose from a range of options, but we do not choose the range of options that we need to choose from. The options we have depend on many factors and circumstances outside of our control. Now, some might point out that it's unclear how we make the choice between these limited options. Perhaps even this choice is somehow predetermined? Some thinkers draw parallels between mysteries of free will and the quantum world. On the quantum scale of reality, a particle cannot appear anywhere, it has limited options, and there is probability involved. But the particle is not making a choice where to appear. Perhaps our choices are determined by probability rather than free will? Here is where I have to acknowledge that my opinion about free will is based on faith (not in the religious sense) rather than on facts. I believe in the importance of making an effort to make ourselves better and make the world around us better (this idea is known in philosophy as "meliorism"). I believe that our power lies in making this effort. We use our personal power by making choices that challenge ourselves, rather than letting ourselves follow the predetermined path or go with the flow. I believe that everybody has some wiggle room where free will can be exercised. In this sense, everybody is powerful, at least to some extent. Each free choice we make determines the range of choices in the next instant, both for ourselves and for others. It's kind of like playing a multiplayer multilevel game: on each stage we have a limited range of options to choose from, and every choice we make opens up new options or closes old options for ourselves and others. I believe that, guided by this view of free will, we can strive to do and be our best under the circumstances. To sum it up: in my opinion, powerlessness and power are always mixed in a way that makes it difficult to say with absolute certainty where power ends and powerlessness begins. Another way to put it: there is no absolute power or absolute powerlessness. That said, it is essential to emphasize that relative amounts of power and powerlessness change from individual to individual and even from action to action taken by a specific individual. So, in specific circumstances, some individuals do have more power than others (which is a concern of scholars studying inequalities). I believe that accepting that we have a certain amount of free will will lead to our empowerment: we will be able to use our power to impact the way things are. On the other hand, I believe that if we acknowledge our limitations and limitations of others (powerlessness caused by determinism), this attitude will foster empathy for ourselves and other, curiosity about all the factors behind people's actions, and humility in the form of acknowledging that no individual can know everything about the way the world works. My position free will calls for alertness. We cannot decide that one person always has more power than the other person and stop there. We cannot say that we know for sure what actions are predetermined and what actions are a result of free choice. Because there are no simple ultimate answers, we need to be flexible in our conclusions and judgements. Alertness in this sense means always wondering what amount of determination (powerlessness) vs. free will (power) there is in any action, in any situation. SOURCES: Brewer, J. (2021). Unwinding anxiety. Avery. ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: Encyclopedia Britannica. (last updated July 28, 2023). Free will. People Who Read People. (January 9, 2021). How does not believing in free will affect one’s life? [Podcast]. (also see the list of sources on the podcast page) Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. (last updated November 3, 2022). Free will.

*This is a new entry of my project POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power.

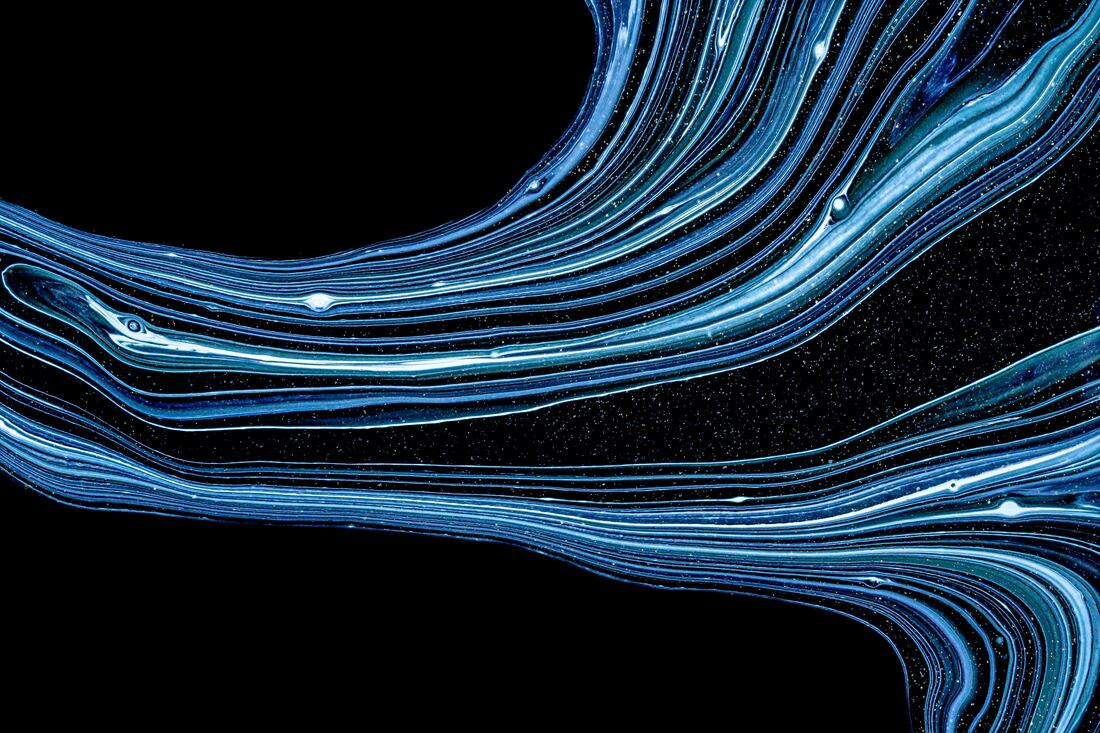

It might not seem like something special, but I believe that it is an essential form of individual power that most people have (but do not necessarily consistently use). It is essential because using this form of power allows us to get some control over our reactions to our own emotions and to things happening around us. When we do not use the power to change the way we see things, we are unable to see the difference between the way we are (the way we feel) and the way the world around us is. When we do not notice that we see things from a certain perspective, we are less satisfied in our everyday lives (according to buddhism, we live the life of suffering). At worst, the inability to tap into this power can lead to bitter conflicts and painful mistakes, to actions that hurt others as well as ourselves. Just to clarify, the term "power to change how you see things" is arbitrary. Like many other concepts and distinctions that I use in this project about power, the term "power to change how you see things" helps me dig into the broad topic of power, but it is just one of many possible ways to talk about it. I could as well talk about "power to recognize that we see things from a certain perspective", or "power to recognize that other people see things differently, and that's ok!", or "power to notice how our perspective is shaped by our backgrounds and emotions". Let me offer an example, a story that illustrates how one can use the power to change the way one sees things. This story comes from my family trip to Rhode Island in the summer of 2022. Rhode Island is one of my happy places (especially when it's warm!). I actually lived there for a few years. Every time I revisit the state, I look forward to spending time by the ocean. All the parents out there know that vacation with small kids is not really a vacation. It is hard work. During my 2022 summer trip, I enjoyed seeing familiar places and faces, but I was also often tired and could not do what I wanted with my day. It was hard to avoid frustration, but I knew that it was important not to let this frustration control how I was experiencing this trip. I was managing this emotion, and it was hard! (This makes sense, since making an effort is a prerequisite of using power.) One morning, I was getting ready to spend some time at the beach with the kids, when tensions and uncertainty crept in our plans. We almost decided to go somewhere else, but eventually I did end up getting to the beach together with the children. However, after the unpleasant beginning of the day, I felt stuck in a bad mood. So here I was, finally at the beach with my kids, but instead of enjoying the warm waves touching my feet I was feeling the waves of frustration rising in my chest. I was frustrated about the morning disagreement with my husband that almost prevented me from going to the beach. On top of that, there was an even worse kind of frustration: the one about finally being at the beach and not being able to properly enjoy it. I knew that I had to make an effort to get out of this vicious cycle of frustration. The first element of power to change how we see things is realizing that we see them a certain way. I was reminding myself about it, but I was still feeling the frustration. The second element was realizing that changing the way I was seeing things at that moment was possible. So I focused my mind on the fact that I was at the beach as I had wanted to and that it was up to me to enjoy it. But I also knew that I needed to be gentle of myself. To be effective, all these realizations and reminders needed to happen without any trace of self-judgement. By the summer 2022, I had been practicing mindfulness for a while, so I knew that I needed to pay attention to the moment, which included my emotions and my surroundings (instead of the circular thought about what the unpleasant morning interaction, about almost not going to the beach, or about my inability to just relax). As I was focusing on my surroundings, which I wanted to experience so much to begin with, I decided to document (via pictures and videos) various little details that I was noticing. This helped me to ground myself in the moment instead of letting the "itty bitty shitty committee" in my head play the "woulda-shoulda-coulda" game. I looked down at the sand I was standing on, with the gentle waves coming in and out. The first thing I noticed was that, each time the water receded, the sand it left behind revealed little patterns that looked a bit like bird's feathers, or perhaps like parts of a plant.

The water was softly coming and going, coming and going. The predictability and gentleness of this movement was calming, but it was never boring because patterns of the sand and of the water were always changing. I noticed that the water carried some sand with it, and the sand swirling in the water created what seemed like small shimmering clouds.

The water was also creating tiny ripples and bubbles. The bubbles were busting and creating tiny circles of ripples that were overlapping in intricate waves and disappearing almost instantly. With its transparent quality, the water seemed like liquid glass decorated here and there with the sparkling whirlpools of sand.

As I was observing this simple natural beauty, my frustration was still there, swelling in my chest. Instead of feeling frustrated about the frustration, I let it be and kept bringing my focus back to the ocean. I was reminding myself that I could see the situation differently, but that it was also ok that I wasn't seeing the way I wanted (not colored by frustration).

So I just kept looking underneath at the softly moving water. Sometimes, I could see small stones or shells buried in the sand. It was soothing to look at the soft lines of water ripples, of the circles left by bursting bubbles, and of small natural objects that the sand revealed.

All this time I was standing in very shallow water. In fact, half of the time, there was no water touching my feet because the waves were coming and going. Next, I moved to a slightly deeper place.

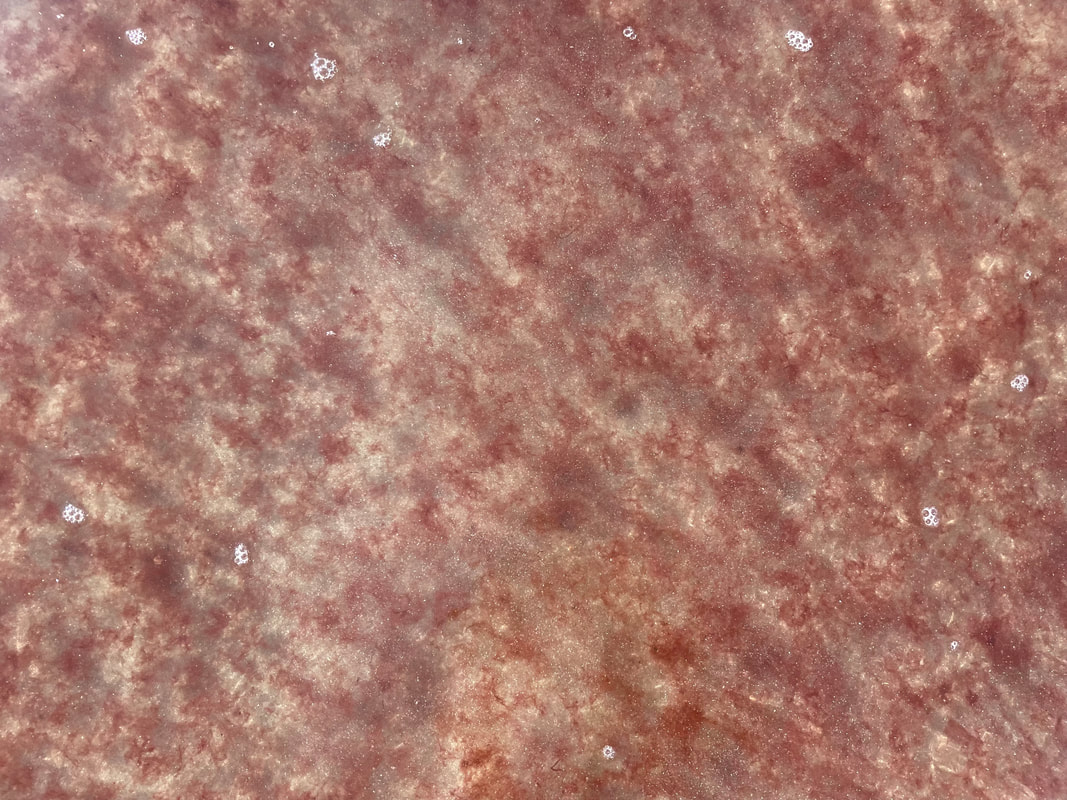

Here I could observe another element: red weed coming and receding together with the waves. Instead of looking closely at the sand, I changed my perspective to see how the water was receding. I noticed that the very edge of the incoming wave was creating a rolling border of sand. I also saw bigger sand whirlpools in the water mixing up with floating fluffy clumps of red weed. The receding water was creating shiny patterns in the sand that looked like fabric.

The seaweed mixing with shimmering sand clouds, with tiny bubbles floating on top, created yet another pattern. Whenever I changed the place I was standing or the angle I was looking from, new details emerged. The more I paid attention to them in the moment, the easier it was to let go of the frustration. I was not forcing it to go away, not telling myself that I need to let it go or that I need to do it faster. I was just letting my emotions go, and it was helping.

There were just so many things happening in the water at the same time! The swirls and the shimmer, little waves and ripples coming in from different directions and overlapping gently, the red weed mixing up with whirlpools of sand, the bubbles and the circles they left, the mysteries of tiny objects (shells and stones) hiding under the water filled with shimmer and color and light.

And then there was sparkles of sunlight that I could see when I looked at the water from yet another angle. The reflection of the sun looked differently whether it was on the sand with the water receding, or on the incoming wave filled with bubbles, red weed, and sand clouds. The sparkles of sun looked like liquid silver; they were hinting at some treasure hidden beneath the water.

I also enjoyed looking at my feet being licked by the gentle waves. My feet, grounded in the sand, were adding more patterns when the water was receding. I felt myself not like a distant observer but like a part of the beautiful play of natural elements that I allowed myself to witness.

I was looking at my shadow, decorated by the living-glass waves, soft bubbles, tiny ripples, and by sand whirlpools mixing with red seaweed. I was a part of the moment, in the moment, and I was feeling happier and more relaxed.

This story is an example of me using my power to see things differently. Admittedly, "things" in this wording is a pretty vague term. I am talking about my ability to see differently the whole situation, but also an ability to see things around me in a different light. I was able to change the focus of my attention from frustration to all the objects and details that make the ocean beach such a special place for me.

Notice that the change of the focus was natural and gentle. I do not think that changing the way you see things can be done by force of shame. I was not telling myself, "Hey, you are at the beach now! Isn't that what you wanted. You should feel better already!" Instead, I allowed myself to remember what I love about the ocean and simply enjoy the moment without self-judgement. It should be clear by now that power to change how you see things is a form of mental power. This is also an example of the power to focus on the now, which is essentially the power of mindfulness. It requires noticing that we see things a certain way and recognizing that the way we see things can be changed. Standing at the beach that day, I was reminding myself that the frustration was coloring how I was experiencing things around me, and that I could experience the moment differently. I was not telling myself, "You can see things differently if you want to" because that would have been a form of self-judgement. Instead, I just told myself, "Hey, this is just the way I see things now, but I can see them differently". This soft reminder helped me, indeed, to see things differently there and then. I believe that anybody can change the way they see things, but the wiggle room of this change is different for different people. For example, a person suffering from depression can probably change the way she sees things to a certain extent, but it is definitely not the same extent that I have. More specifically, a person suffering from depression would find it very hard - by the nature of this condition - to recognize that when things seem hopeless, this is just how she sees them. (Just to clarify, I know very little about clinical depression, so my ideas about it might be erroneous.) Even if we do not imagine such a challenging circumstance as depression, for an average person changing the way he sees things can be very difficult. That is to say, one cannot easily see things in any possible way. The way we see things is determined by our environment (culture and upbringing), by individual features of one's physiology and psychology, as well as by specific circumstances. We are not entirely free to change the way we see things any way we choose. In this sense, it would be unfair to expect another person to easily change their perspective in the way you think would be beneficial for them. I might think that it would be helpful for my child not to be afraid of vampires under his blanket; but it would not be fair for me to assume that it would be easy for him to recognize that there are, indeed, no vampires hiding there. Changing the way we see things is determined by many circumstances outside of our control as well as by some things within our control. I believe that most people have some wiggle room, and that’s where their choice to change the way they see things can happen. But who's to judge how big this wiggle room is? Because changing the way we see things is a form of mental power, it is an invisible power so we often don’t know that we have it, and if we use it, it might not be obvious to ourselves and others. |

SIGN UP to receive BLOG UPDATES! Scroll down to the bottom of the page to enter your email address.

I often use this blog to share new or updated entries of my hypertext projects. If you see several versions of the same entry published over time, the latest version is the most updated one.

|