|

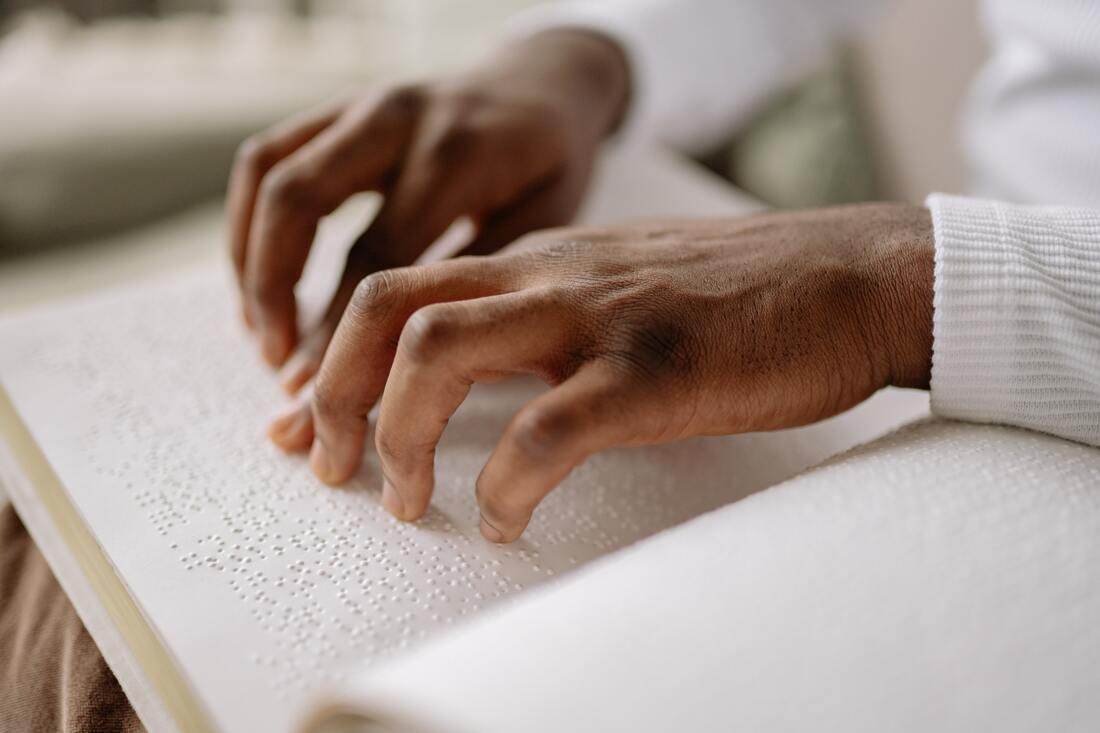

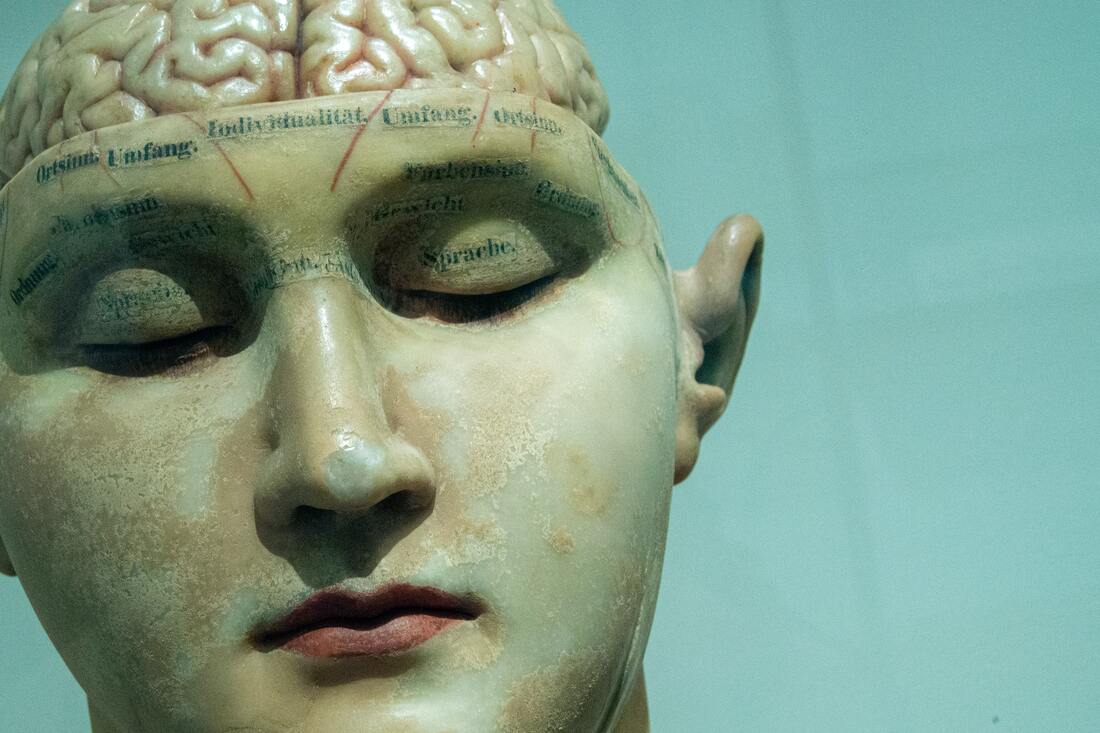

*This is an entry of my hypertext book POWER of meanings // MEANINGS of power. Obviously, one can look for a definition of power in a dictionary. For example, here. However, understanding this concept requires more than just reading a Merriam-Webster entry. Many scholarly books have been written about power. This page will reflect my attempts to come up with my own working definition. The focus here will be on what I call "social power" which exists through people's actions and relationships. Power in the “social” sense is different from other meanings of this word, such as magnification or an order of angels in Christianity. (I believe that it is worth exploring the meanings of power that are not directly related to people and relationships between them. Arguably, such exploration can help us better understand how human beings make sense of themselves, for there must be a reason why the word “power” acquired these additional meanings.) When we think about social power, some words that come to mind are: ability, capacity, authority, control and force. (These synonyms of power deserve a separate investigation.) They can be roughly associated with two different aspects of social power – ability and influence. These two aspects do not really exist apart from each other, but can be viewed separately for the purpose of my analysis. To be more precise, "ability" and "influence" are two different angles one can take when looking at power. The first aspect provides the focus on the individual: what he/she can do. The second aspect provides the focus on relationships between people: how an individual's actions affect others. 1) We can view power as one's ability unrelated to other people's abilities and actions. "Ability" is a fundamental aspect of power. It is telling that in some, but not all, languages the word power has the same root as the verb can. We will start start by talking about physical abilities. They can be roughly divided into abilities of body and mind (this division is a simplification, because our mind is a function of the brain, which is a part of the body). Some of these abilities are sometimes called "power", but other are not. For example, we can see references to "the power of sight", such as in the following statement: "The power of sight is often taken for granted, but it greatly affects a person's quality of life". On the other hand, although the walking is also a physical ability, such phrase as "the power of walking" seems to make less sense. Why can we view physical abilities as unrelated to other people's abilities and actions? It is possible, because a person can have this power and use it regardless of whether somebody else can or cannot do that. "Seeing" or "walking" is not a limited resource. For me to be able to see or walk, I do not have to take something from others. (Interestingly, fictional narratives can have an antagonist who steals somebody else's energy in order to support one's own physical abilities.) Thinking physical abilities as power allows us to talk about intentionality. Indeed, power comes not just from having an ability, but from using it in a certain way, which requires as intention. There is a difference between passively watching and actively seeing. Intentionally using our physical abilities is fundamental for being human, or, more specifically, for being a living human being. A person whose body fulfils basic physical functions without intentionality is as good as dead, because this person does not have an ability to act (see Power on/off). Viewing power as physical abilities unrelated to other people's abilities and actions is crucial for two additional reasons. First, it's important to discuss how we take most of our physical abilities for granted – until we lose any of them, that is (see Privilege). Second, in some cases, power understood as a physical ability does become related to other people's abilities, often in ways that go unnoticed for those who have power (e.g., the power of speech). Thinking about intentionality allows us to consider how abilities are used and how they can be improved through learning. This, in turn, allows us to see the following three levels related to what our bodies/minds can do: Level 1: Bodily function that exists without intentionality and cannot be improved. A person with brain damage in a vegetative state can have his eyes open without seeing. Level 2: Intentional use of this bodily function becomes an ability. I choose what I look at and react to what I see. Level 3: Understanding how the ability works allows me to hone my skills. I can train myself to notice certain things, to cognitively process what I see in a specific way, etc. Only the second and the third levels can be seen as power, because they are associated with things we can do. Another example: We do not talk about the "power of breathing" when we discuss the bodily process that is indispensable for being alive. However, we can talk about purposefully practicing different ways to breathe: for example, slowing down or focusing on our breathing as part of a meditation. In this case, it makes sense to talk about the power of breathing, as we choose to breath in a certain way. Because power is impossible without intentionality, understanding power requires exploring the concept of free will. Thinking about physical abilities as power that requires intentionality means considering our choices. Indeed, one can choose to use her physical abilities in a certain way. That's what makes them abilities and not simply bodily functions. I can choose to see some things but not others, to speak over other people, to walk in a certain direction in order to achieve specific goals. I can also choose to view my abilities as skills that require improvement (e.g., breathing). So far, all the examples above were about physical abilities of our bodies: seeing, speaking, walking, breathing. These abilities are more visible that what we can call "mental abilities" (same as physical disabilities are more visible and taken care of than mental ones). Remember that mental abilities are just a type of physical abilities, since the brain is a part of our body. Below, I will compare physical abilities and mental abilities, keeping in mind that this division is artificial. It's easier to talk about physical abilities because their outcome is often visible and directed outward. For example, I can have the power to lift a heavy rock. In contrast, mental abilities are much less visible or measurable. Many of them can even be difficult to describe.

When we think about mental abilities, we imagine intelligence. However, considerable disagreements exist on what counts as intelligence, as debates about the IQ test reveal. Some note that people have multiple intelligences, while others disagree. Debates have raged about mental abilities related to different spheres of life. Are women better at empathy while men are better at math? Two other well-known mental abilities are logic or memory, none of them simple or straightforward. Other mental abilities may not even have specific names, which does not mean that they are less important. For example, there is no word (in the languages that I know, at least) for an ability to choose a certain interpretation of a situation or an ability to react to circumstances in one way rather than another. However, arguments are made about the importance of these abilities for our well-being. Same as with physical abilities, one can explore different levels of mental abilities, raging from a function to an ability that can be improved. For example, we can talk about biases as functions of our brains (Level 1) that are indispensable for being human and staying alive. We can train ourselves to be aware of these biases to avoid pitfalls of our brain's mechanisms (Level 2). Finally, we can strive for self-awareness of higher order by constantly educating ourselves about the way our biases affect ourselves and other (Level 3). Recognizing the role of intentionality in our mental abilities allows us to work on improving them. Improving our mental abilities can become a source of strength –power. However, in this case we should also carefully consider questions of individual free will, choice and responsibility. Since mental abilities are so difficult to properly understand, it is not yet clear which ones we can/should improve and to what extent. 2) Power as one's ability as related to other people's abilities. In contrast with the first aspect, this one is not about what an individual can/cannot do. It is about how this "can/cannot" will impact others. It means focusing on relationships and bringing in such terms as influence, force and authority. Unlike the first aspect, the second one is impossible to discuss without referring to the idea of limited resources. For example, my ability to speak (and be heard) is directly related to somebody else's inability to speak (and be heard), because not everybody can speak (and be heard) at once. In this sense, one person's ability becomes possible through somebody else's inability or can lead to another person's inability to do something. This second aspect of power has been the main focus of scholarship on power and it the main reason for the interest in power to begin with. This is not surprising: we live in the world of limited resources, both tangible and intangible ones. In this context, one person's ability to tap into a resource often means another person's inability to do that, which can be – understandably – seen a problem (see Inequality). Tangible resources include objects that we need to satisfy our physical needs. What happens if there is one apple on the table, but two of us who want to eat the apple? One person's ability to eat the apple means the other person's inability to do so. Intangible resources include time and attention. We have only a certain amount of hours tonight to do something together. I want to go to the cinema. You want to go to the restaurant. If we do what I want, my ability to choose will equal your inability to do so. The environment each person exists in is a combination of tangible and intangible resources that are all limited. In any specific situation, one person can only get her needs fully met if another person does not get her needs fully met. To put it differently, not everybody can be satisfied all the time. We can say that whoever gets their needs met is the one who has the power in this specific situation. Another way to explain the idea above is that not everything can happen at once at the same time. Objects exist in space in one specific way in each specific moment. Each moment, my actions determine that some things will exist in a certain way rather than another. Some of my influences may seem irrelevant or unimportant; yet, they all matter in the grand scheme of things in ways I may never fully comprehend. My actions inevitably influence other people and also clash with their influences. Understanding how we all influence each other requires tapping into the chaos theory. We can think about power as influence of an individual. At the same time, bigger patterns that explain interactions between different groups or people should also be explored. This exploration is as important as it is prolific. Such major names as Marx, movements as feminism and scholarly frameworks and critical race theory are all related to understanding power through its second aspect (as outlined on this page). Power as influence will be discussed in more detail in other parts of this hypertext book. *** By taking apart these two different aspects of power, I was hoping to show why I believe that “power” is not homogeneous one-piece something that one can either have or lack. Each person has a variety of abilities. Each person occupies constantly changing social context filled with other people and all kinds of limited resources. So, it may be more accurate to talk about powers in plural. Each of us possesses a constantly changing combination of those. In this sense, calling somebody powerful or powerless appears to be a gross simplification. We tend to think about power when we discuss who won a war, who is physically stronger or weaker, who forced whom to do what, etc. In other words, we pay attention to visible forms of power. I believe that understanding how power works is impossible without paying close attention to seemingly trivial situations and everyday interactions that may not even seem to have anything to do with power relations. These situations reveal the multiplicity of powers we all possess, albeit in different combinations, that are in a state of constant flux.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

SIGN UP to receive BLOG UPDATES! Scroll down to the bottom of the page to enter your email address.

I often use this blog to share new or updated entries of my hypertext projects. If you see several versions of the same entry published over time, the latest version is the most updated one.

|